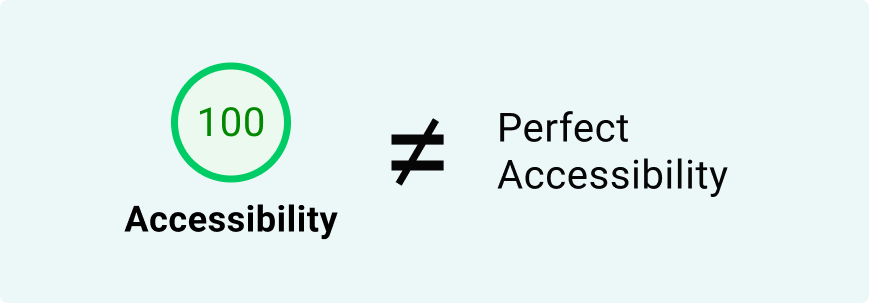

When you’re working to make a webapp, enterprise software tool, or even a hardware interface accessible, automated accessibility checkers, like Axe, WAVE, Lighthouse, and others can be incredibly helpful. They catch many of the WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) violations, especially those that are clear-cut and rule-based.

But here’s the thing: accessibility is about people, and people are nuanced. Not everything can be boiled down to a checklist or a script. There are many accessibility issues that require human judgment, and unfortunately, automated tools often miss them.

If you’re relying on automation alone, here are 10 important categories of WCAG violations that could be slipping through the cracks.

Automated tools are good at flagging missing alt attributes—but not at judging whether the alt text is useful or appropriate.

For example:

<img decoding="async" src="data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E" alt="image" data-lazy-src="dog.jpg"><noscript><img decoding="async" src="dog.jpg" alt="image"></noscript>

Technically valid, but totally unhelpful.

Even worse, tools can’t tell when an image is purely decorative and should have an empty alt="". That’s a decision only a human can make based on context.

Checkers can detect basic contrast issues, like dark text on a light background. But they struggle with more complex layouts, such as:

Text over background images or gradients

Text embedded within images

Text inside hover or modal components that appear dynamically

It’s possible AI might get better at this, but in the meantime, it’s best to grab the eyedropper tool and check the colors in areas with suspiciously low contrast.

WCAG requires that content appears in a meaningful order, especially for screen readers. Tools can analyze the DOM, but they can’t confirm:

Whether the reading order makes sense

If the visual layout matches the logical flow

This matters for people navigating with keyboards or assistive technologies.

You can find this by using a text-to-speech tool and verifying that the spoken content matches the order of written content. All you have to do is highlight the text and select “Speech” > “Start Speaking.” You should also very the content matches the order “Reading Mode.”

Checkers can detect if elements are focusable, but that’s just part of the story. They can’t:

Verify whether custom components are operable via keyboard

Test the logical tab order

Detect keyboard traps (places where users get stuck)

Manual testing with just a keyboard reveals these problems fast.

WCAG guidelines state that media, such as video and audio content should have alternatives.

Most checkers do not verify:

Whether captions are included in the video

If a transcript is provided

Verify that all of your videos have live captions and any audio content, like podcasts, has a transcript available.

Sure, a tool can check if a label exists. But it can’t:

Tell if the label is clear or contextually helpful

Confirm that it’s programmatically associated (especially in custom form setups) Humans know if “Name” means first name, last name, or something else entirely.

For example, take a look at this “Forgot Password” screen from a state government web app:

Technically, those inputs have labels, yes. Are they helpful? No.

ARIA can help—or hurt—depending on how it’s used. Tools may flag incorrect ARIA syntax, but they can’t tell if:

It’s the right use of ARIA

It actually improves the experience

Overuse or misuse of ARIA can confuse screen readers more than it helps.

WCAG guidelines recommend content that’s clear, readable, and understandable.

But no tool can tell if:

The writing is free of jargon

Instructions make sense to your target audience. This is about empathy and clarity—not just code.

Most accessibility checkers run in a desktop browser. They don’t assess:

How the site behaves at 200%+ zoom.

Whether it works with mobile screen readers like TalkBack or VoiceOver

If touch targets are large enough for users with mobility needs

You’ve got to test on real devices or simulators.

Automated tools can catch missing required fields or improper form labels—but they don’t know if:

Error messages are clear and specific

Users can recover easily after an error

Instructions help users avoid mistakes in the first place

Usability is about guidance, not just validation.

Automated accessibility checkers are a great starting point, not a finish line. They save time and catch common issues—but they don’t replace human insight.

To truly build inclusive digital experiences, pair automation with:

Manual testing

Keyboard navigation checks

Screen reader reviews

Real user feedback

Because accessibility isn’t just about compliance—it’s about creating better experiences for everyone.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |